What Your Church Gave Up When It Gave Up Hymnals

From my vantage point, the modern so-called “worship wars” that characterized the 1990s and early 2000s are over. You remember those, right?

As the seeker-sensitive movement ramped up its stranglehold on modern Christianity, pastors found themselves in a difficult position trying to accommodate the biblical traditions of their past while leveraging the apparent power of the new methodology. In this new approach, sermons were replaced with “talks,” preaching was replaced with “sharing,” pews were replaced with chairs, libraries were replaced with coffee bars, and ultimately, God’s glory was replaced by man’s “felt needs.” The old, stodgy particulars of yesteryear were traded out in favor of new, trendy accoutrements. And the results spoke for themselves—unbelievers (the supposed “seekers”) loved it, gathering in droves for a worship service centered around them rather than God.

Of course, the underlying philosophies behind this change began even a few decades prior, as John MacArthur recounts:

Prior to the 1960s no one expected a church service to be entertaining. No one wanted to be told to touch their neighbor and repeat a trite phrase suggested by the preacher. No one thought of worship as a physical stimulation. No one dreamed of using flashing lights and smoke to set the atmosphere in a worship service. No one demanded to be told that God accepts them just the way they are.

When you went to church you expected to be thoughtful and quiet—prayerful, sober, reflective. The service was ordered so that the word of God was central. It was read and proclaimed with the aim of leading you to understanding, conviction, transformation, and elevation. The structure was deliberate, and the objective was for people to have an encounter with God through an understanding of his truth, with an opportunity to express it in corporate worship.

But by the time large-scale protests and student rebellions came into vogue in the 1960s, some of the experts were already telling church leaders that God-centered worship, sober reverence, and serious preaching from the Bible about sin and holiness are all far too absolute, too narrow, irrelevant, and possibly even offensive to the culture in which we live. Young people were seeking “authenticity” (sin and all), and they had no interest in sanctification, holiness, purity, godliness, or separation from the world.

Because many church leaders were not well grounded in Scripture and sound doctrine themselves, they were susceptible to those ideas. They lost sight of the fact that their job was not to make unbelievers happy with the church; it was to feed and lead and guard the flock of God—and to teach the saints to be like Christ.

With the noticeable growth in attendance produced by seeker-sensitivity, birthing literally hundreds (if not thousands) of mega churches, average pastors who took notice decided that they too, needed to capitalize on this shift. And that’s when the worship wars began. After all, the older, wiser congregants easily saw through the facade offered by seeker-sensitivity, recognizing the wisdom of long-held practices. At the same time, pastors wanted to reach and retain the younger, more energetic demographic in their congregation. Battles raged and opinions flared as one group wanted to keep its former practices while the other wanted to update virtually everything about the local church worship service.[1]

All that to say, once new pragmatism came into contact with old piety, fireworks were inevitable. Churchgoers with different views made those views abundantly clear to one another. The war was on.

Sadly, one incredibly wrong-headed idea to achieve a ceasefire was to create two distinct services on Sunday: one called “traditional” and the other called “contemporary.” The traditional service was earlier in the morning, continuing in standard evangelical practices of the past, whereas the contemporary service was held later in the day, incorporating what could only be called an entire “set change” to the church building.

Yet, it doesn’t appear that such a piece-meal ecclesiology proved to be a long-term solution. Sure, there are likely still some churches even today that continue holding such vastly different kinds of services. But as far as I can tell, most churches that initially created two services either became two churches, or subsumed one service into the other. Such a stark dichotomy was too much for any given local church to bear forever. The weekly worship wars that characterized many churches came to a close. And the winner is clear: contemporary.

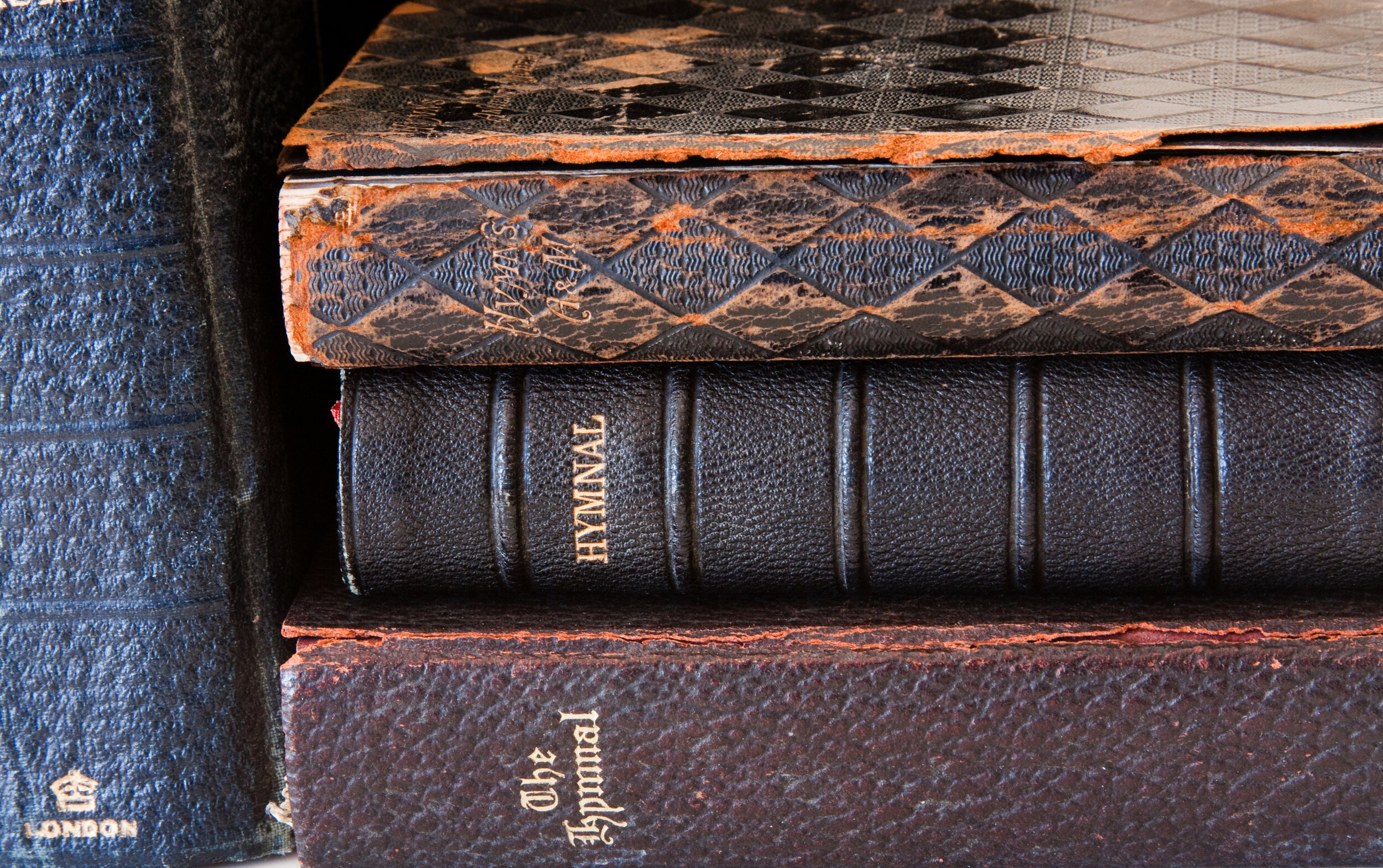

Unfortunately, even if your church survived the battle without many scars, it likely suffered at least one casualty: the hymnal. Slick, adaptable, high-visibility projection screens—trademarks of the PowerPoint preaching begun in the ‘90s—were simply too irresistible for most local congregations to avoid. The question is, was this change nothing more than a cosmetic difference? You be the judge.

Here are some things I think your church may have given up when it gave up hymnals.

1. A Connection to Church History

Though it would undoubtedly be argued that projectors are simply a medium that can provide the same content as a hymnal, the obvious reality is that one of the intended advantages of the projector is its ability to utilize the latest and greatest music—an advantage which, ironically, is also a disadvantage, because it tends to sever the congregation from the past. When your congregation joins in song together, there’s something spiritually significant about knowing you’re singing the same soul-searching songs as saints of the past. Whether it’s “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” or “Holy, Holy, Holy! Lord God Almighty,” the songs found in a typical hymnal are naturally tied to history by virtue of their physical binding. And in many cases, this tie to history comes from more than just a musician who was paid to write a new jingle, but is a song forged in the fire of life’s difficulties. In fact, an even closer—and perhaps more significant—connection to church history also occurs when a grandchild picks up and sings from the same pew hymnal used by his or her grandparents. I fear that such a tangible legacy of faith simply cannot be duplicated by a flat screen on the wall.

2. An Immunity to Theological Fads

Pastor Joel Beeke is right when he says, “Sing doctrinally pure songs. There is no excuse for singing doctrinal error no matter how attractive the tune might be.”[2] As a companion to the first point, another benefit to using a hymnal over its electronic counterpart is that it’s immune to theological fads. Make no mistake about it: I don’t mean to say that a hymnal is immune to theological error, as if hymnals are infallible. But they are immune to the latest tripe that finds its way onto Christian radio stations in a way that projectors and other electronic forms are not. As a bound, fixed book, the hymnal can’t be hijacked by the overzealous music leader who wants to introduce his church body to the latest song he jams out to in his car. Here it must be stressed that the point is not whether electronic screens can be spiritually safeguarded by a more discerning music director in order to provide the same level of immunity as a hymnal. The point is that the hymnal—being a fixed canon of song—has that advantage inherently. The unholy trinity of Jesus Culture, Bethel Music, and Hillsong may have free reign over the airwaves, but not over the paper hymnal. It must be said, of course, that this doesn’t mean all new songs are worthless. On the contrary, it was only a few years ago that the late Dr. R.C. Sproul penned over a dozen new hymns, at least one of which (“The Secret Place”) has found its way into Hymns of Grace, an excellent modern hymnal published by The Master’s Seminary Press.

3. A Guard Against Shallow Music

Undoubtedly, one of the most noticeable shifts in Christian music over the past few decades is the sheer volume of shallow music. As the modern evangelical church embraces a “love-only” god, the music it produces plays the same one-string banjo. Look at what constitutes Christian music these days and the downgrade is obvious. One popular worship song from just over a decade ago contained the notorious line, “So heaven meets earth like a sloppy wet kiss and my heart turns violently inside of my chest,” along with an unsurprising “Whoa, how he loves us” phrase repeated ad nauseum at the end. A more recent hit song from just a few years ago speaks of the supposed “overwhelming, never-ending reckless love of God,” which is, of course, more an atrocious assault on God’s omnisapience than a helpful affirmation of His love. As the general sentiment toward sound doctrine wanes, so does the commitment to lofty music. Shallow theology has produced shallow doxology. This stands in stark contrast to that which an average hymnal offers. Flip to the topical index at the back of a hymnal, and you’ll see songs dedicated to sanctification, atonement, judgment, and missions, among dozens of other sober-minded aspects of the faith. Charles Wesley, for example, once wrote a hymn that contains a plea to God for a tender conscience, saying, “I want a principle within, Of watchful, godly fear, A sensibility of sin, A pain to feel it near.”[3] It’s not merely that hymnals are able to guard against shallow music; they’re intended to. Since hymnals typically contain songs written by pastors and theologians of bygone eras, it makes sense that the music and lyrics would be of the same caliber. And with that depth of doctrine comes a theological vocabulary that equips the congregation with something more than a “sloppy wet kiss.”

4. A Teaching Guide for Music Literacy

In most cases, projectors are to songs what microwaves are to meals. Sure, they get the job done in so far as they provide the congregation with the lyrics to the songs—but rarely, if ever, do they provide the actual notes to the song. Quick and easy, the worship music on a screen often lacks the same substance musically as microwaved meals lack nutritionally. Since the modern music shift also emphasizes the guitar—often with basic chord progressions—over the piano, this noticeable lack isn’t seen as problematic to most. And yet, the underlying assumption in this shift is that the congregants already know the melody. If they don’t, they’ll just have to mouth the words until they pick it up, because there’s almost never any musical notation that accompanies the lyrics on a screen. Note values, rest values, and time signatures are absent, not only making it difficult to pick up and go along with the rest of the congregation, but also reinforcing the same music illiteracy that has taken over this generation. Even for someone like myself who is not all that musically inclined, the hymnal serves as a guide to stay on beat and in key. While it could be argued that an electronic screen could technically provide the same musical notations as a hymnal, that argument is as compelling as saying that a microwave could technically provide a nutritionally dense, full course meal. Let’s face it: form and function are more intimately connected than we’d like to admit.

5. An Audible Expression of Unity in Diversity

As an additional consequence to the aforementioned lack of music literacy, the notationless lyrics of the projector provide no additional insight for singing harmony. Gone are the days in which a song hits a crescendo and the congregation’s four-part, choir-led harmonies belt out in glorious praise to God. Hymnals provided that opportunity. Instead, flat screen lyrics breed flat screen melodies. There is little vocal texture offered when all congregants are singing the same part. Lest someone view this as nothing more than a superficial preference, it should be pointed out that such unity in diversity is precisely what is afforded by the Gospel. As Christ saves people from every nation, tribe, and tongue (cf. Rev. 7:9), having torn down the wall of hostility between Jew and Gentile (cf. Eph. 2:14), the one-body-with-many-members motif (cf. 1 Cor. 12:14) finds wonderful expression in the soprano, alto, tenor, and bass vocalists. I fear that without the hymnal, this opportunity is gone in most churches. Is this nothing but a cultural preference? Consider this: even if it is, it is the same culture that once had a hymnal that has now abandoned it, which means this is not a comparison of different cultures, but a comparison of one culture with its former self. By way of analogy, it would indeed be wrong for a father to compare the efforts of one of his children with another, knowing that they have different strengths and weaknesses, but it would not be wrong for a father to compare the efforts of one of his children with what he knows of that child’s own potential.

6. A Technologically Impervious Medium of Communication

“Hello? Can you hear me? Mic check. Testing, 1, 2, 3!” You know the routine when one of the microphones on the platform doesn’t work during the church service: the entire congregation turns around to see either a sound guy frantically pushing buttons and moving sliders in order to get the service back in motion, or a sound guy who is asleep at the wheel and doesn’t realize that all eyes are on him. While technology can indeed be a blessing (especially when it comes to amplification), the reality is that the modern church’s dependence on it is far too extensive at times. And that is all the more apparent when it comes to corporate singing. Not only is a congregation dependent upon all of the electronics used for the audio component of the worship music, but the visuals as well. Rather than each individual taking responsibility to keep up with the rest of the church body by using his or her own hymnal, the entire congregation is held hostage to both an attentive PowerPoint operator and a non-malfunctioning electronic display. And when either of those two fall through, corporate singing is liable to come to a complete standstill. When the lyric slides don’t advance, neither does corporate worship, sadly. Let’s be honest: these kinds of disruptions during the worship service are unnecessary. Hymnals stand the test of time by providing the church with a medium of communication that requires nothing but ambient light and ready hearts.

7. A Ready Tool for Ministry

Ever wondered what songs you should sing together as a family during family worship time? Or needed quick access to songs of hope when ministering to suffering patients in a hospital? Or wanted to provide an opportunity for a grieving family to express their hearts to God at a graveside? No, of course not. Those are things that only pastors—“professional Christians”—do, right? Wrong. One final fear that I have with regards to the discarded hymnal is that it serves as an indictment on a vast majority of Christians who are not engaged in the kinds of ministries that would be greatly assisted by such a tool. In other words, if you are a dad looking to lead your family in song at home, the hymnal is precisely the resource for the job. You can quickly check the Scripture index at the back to find a song that matches the passage of Scripture you just taught your kids that day. Or, if you get a call that someone is in serious medical trouble at a nearby hospital, you can throw a hymnal into the back of your car and hit the road. The songs that refreshed your heart can be used to refresh others. Or, if you want to bring the gift of music to a funeral service, wherever it may take place, a stack of hymnals gets it done. The minds of those who are mourning can be turned upward through song to the God who knows their heartache. On the other hand, good luck lugging a projector or flat screen television to the occasion (and no, gathering a group of people around a three-inch cellphone screen isn’t a realistic option either!). At the end of the day, one of the greatest blessings in getting familiarized with a hymnal on Sunday mornings is that it then serves the believer well in the ministries he or she should be doing throughout the rest of the week.

Deprived of the Best Expressions of the Gospel

With these things in mind, some might view the aforementioned points as purely surface concerns. After all, historically speaking there have been hymnal-sticklers who advocate for strictly a capella worship music. And even with the shift away from that perspective, it has taken many people a long time to overcome a “drums are of the devil” perspective. I would agree that those kinds of commitments to the hymnal are, in fact, little more than superficial traditions with no biblical support. But in looking back over what has been lost, it should become evident that it is the principles underlying the use of a hymnal that are actually at stake—the hymnal is just the tangible expression of those principles.

Others might respond to these concerns by rejecting both hymnal and projector, saying instead, “Well, that’s why our church takes an Exclusive Psalmody position!” For them, the question is not whether hymns should be sung from a book or from a screen, but whether they should be sung at all. This position, which advocates for strictly the book of Psalms to be used in corporate singing, rightly identifies the problems with fad-driven worship music, but responds to it in a way that I think limits, rather than benefits, corporate expressions of praise. Academic theologian Derek Thomas explains, as follows:

If you adopt an exclusive Psalm-singing position (as my son-in-law would, and belongs to the Covenanter tradition, and loyally and faithfully maintains that position to this day), that means that you can sing about Jesus in pre-fulfillment terms, but you can never say the name “Jesus.” You can preach the name “Jesus,” you can pray the name “Jesus,” but you can’t sing the name “Jesus,” and that doesn’t make sense to me. If you only sing the Psalms, you’re always in the shadow; you’re always in anticipation mode. You’re never in fulfillment mode.[4]

In other words, a Psalms-only perspective keeps the church away from the nonsense that plagues modern evangelicalism, but also keeps the church away from music that explicitly speaks the name “Jesus,” and in ways revealed in the New Testament. Indeed, hymns based on New Covenant realities are helpful for church life (cf. Eph. 5:19).

There is more that could be said, but having offered a diagnosis, I’ll give Dr. Sinclair Ferguson the final word:

I don’t know that I ever went to a church, maybe until I came to the United States of America, where we did not use a hymn book. And again, this may sound slightly grungy, but I feel the loss of a hymn book is one of the greatest worship tragedies of the current Christian church for this reason: a hymn book provides a kind of discipline on worship. People know what they’re not singing, as well as what they’re singing, whereas, I think, in what usually privately I’ve come to describe as this ‘screening’ of the evangelical church, we don’t know what we’re missing. Somebody somewhere is choosing that we sing these things, and often, I think in many churches, we deprive ourselves of twenty centuries of the best, simple expressions of the Christian gospel.[5]

[1] John MacArthur, Sanctification: God's Passion for His People (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2020), 60-61.

[2] Joel Beeke, ed., Family Worship Bible Guide (Grand Rapids, MI: Reformation Heritage Books, 2016), xvi.

[3] John MacArthur, Stand Firm: Living in a Post-Christian Culture (Sanford, FL: Reformation Trust Publishing, 2020), 23-24.

[4] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0rWT2rNyUHo

[5] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fbgiahq39Rc